I think it’s safe to say that the last 18 months have been a whirlwind for most of us, but especially the 2024 recipients of the Global Raptor Grant (GRRCG). This cohort of grantees worked diligently to better understand some of the world’s most at-risk raptors in the face of political turmoil and rampant inflation, on top of all the standard challenges of conducting research in wild and often remote spaces. In spite of it all, they’ve each closed key knowledge gaps for four at-risk species, laying the foundation for the conservation of these endangered and vulnerable species.

Sergi Epsi, Chaco Eagle, Argentina

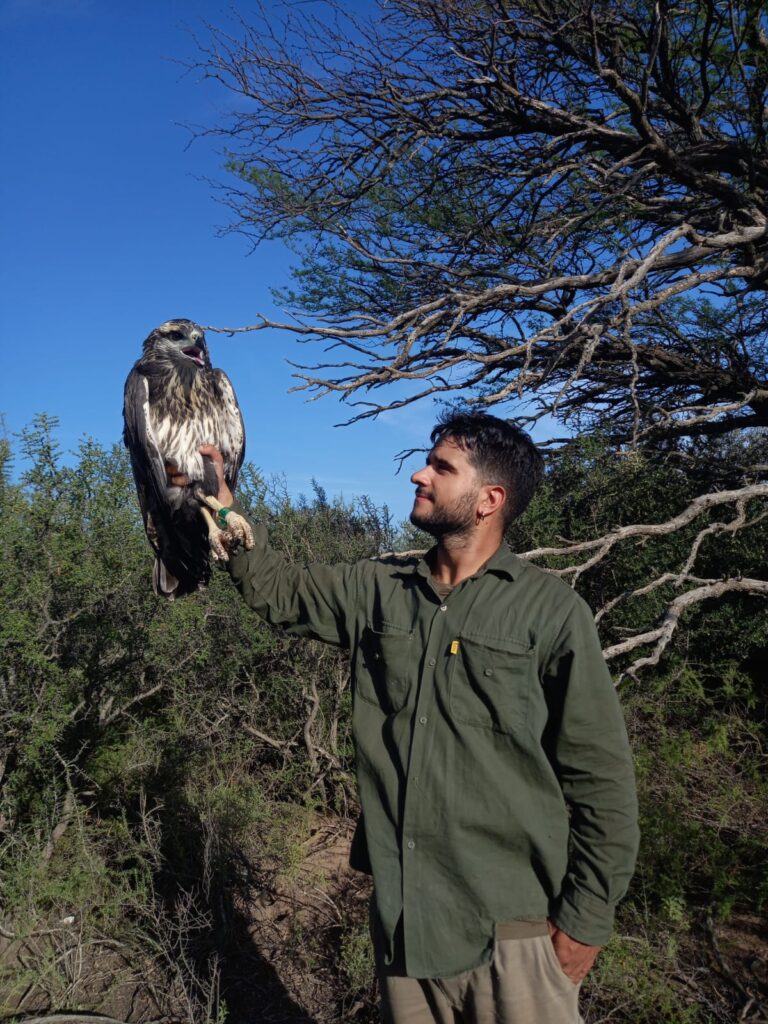

Sergi Gómez Espí’s research on the Endangered Chaco eagle in Argentina’s Pampa province revealed key insights into the species’ nesting behavior and diet that will be vital to the conservation of this endangered and slow-to-reproduce species. His team found that nest sites were strongly associated with snake abundance in low-desert shrublands, where moisture was low and vegetation moderately productive. Camera trap data showed that chicks were fed mostly snakes and armadillos—both low-mobility prey—highlighting the importance of preserving habitats rich in these species.

Despite economic and political upheaval that caused costs to rise by 300% and limited fieldwork, Sergi made the best of his circumstances by reconnecting with local landowners and discovered two new nests. He also raised awareness about rescue ramps—tools that prevent eagles from drowning and contaminating landowners’ water—and the eagle’s role as a top predator. Sergi plans to expand outreach in schools and search for nests in the Espinal biome, one of South America’s most threatened regions.

Sergi holds a Chaco Eagle after banding

Bruktawit Kibret, Secretarybird, Ethiopia

A Secretarybird flies into a nest

The Endangered Secretarybird is one of Africa’s most charismatic and evolutionarily unique birds of prey. It’s also one of the least studied, particularly in Ethiopia, where Bruktawit Kibret spent the last 18 months conducting the first-ever study of the ecology and distribution of the species in the country. Bruktawit and her team confirmed 21 breeding pairs within her study area, Hallaydeghe Asebot National Park. She also used advanced ecological modeling techniques to map current habitat suitability across the country for Secretarybirds. Leveraging several climate change scenarios, Bruktawit also mapped what habitat will likely be suitable for the species by 2070, finding significant losses of suitable habitat.

Despite facing security challenges and budget setbacks, Bruktawit also worked towards her other objectives, advancing community engagement and building momentum for ecotourism. She hired and trained local assistants who have now secured permanent employment, raised awareness about how Secretarybirds and humans can more peacefully coexist, and developed a partnership with park leadership to use ecotourism to generate income for the local communities. With two scientific papers ready for submission and plans to complete the social survey by 2026, Bruktawit is excited to continue her work to understand and conserve this incredible raptor as she works towards her PhD.

Panji Akbar, Javan Scops Owl, Indonesia

Panji deploys an ARU

In 2022, researchers discovered a new range for the Vulnerable Javan Scops Owl—the Gunung Sawal Wildlife Reserve in Indonesia. Panji Akbar and his team used passive acoustic monitoring to uncover 31 Javan Scops Owl sites—plus four other owl species, two of which had never before been documented in the reserve—during 2,200 hours of recordings.

By pairing these findings with advanced habitat modeling, the team mapped 3,536 hectares of suitable Javan Scops Owl habitat and found that a quarter of it lies outside protected areas, highlighting the need to extend conservation beyond reserve boundaries.

The project also strengthened community involvement in conservation. Local guides helped deploy recording units and received GIS training that supports sustainable resource use. These partnerships are central to Cikananga Wildlife Center’s long-term vision for the region, which includes developing alternative livelihoods for the local community, such as creating bird-friendly agricultural products and developing avitourism, and expanding biodiversity monitoring. The team plans to continue their acoustic surveys to better understand how Javan and Sunda Scops Owls share their forest home and to use their findings to shape education and conservation efforts across West Java.

Kaushal Patel, Forest Owlet, India

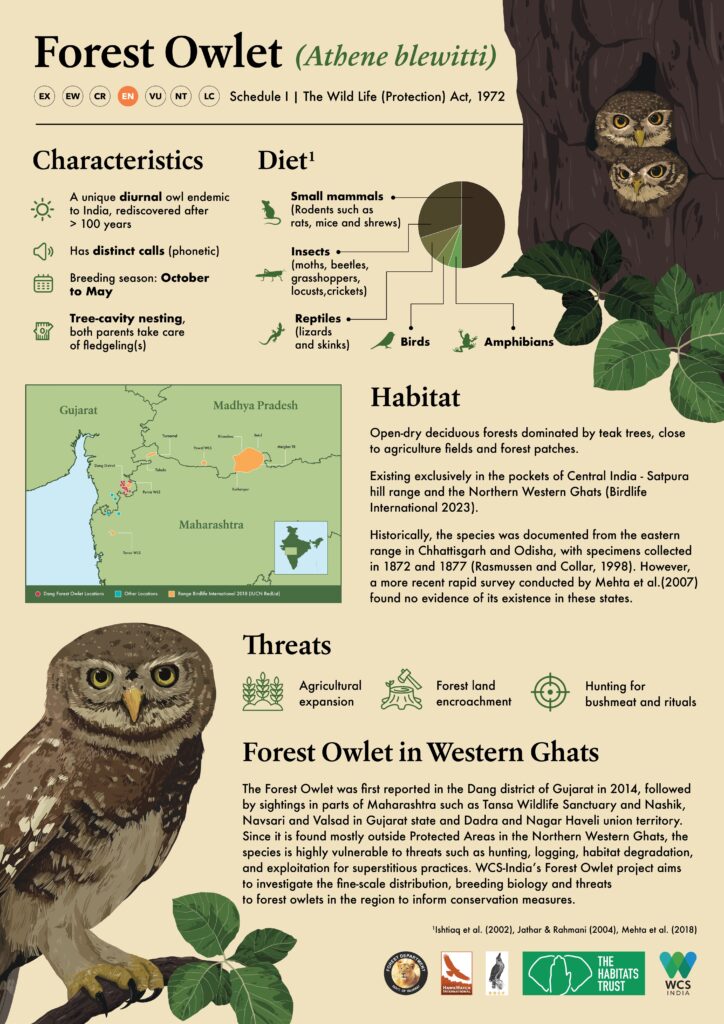

Forest Owlets were once thought to be teetering on the edge of extinction, but recent research by Kaushal Patel and other biologists paints a much brighter picture for this Endangered owl species. Kaushal and his team at WCS-India spent the last 18 months documenting the presence of Forest Owlets in India’s Dangs forests, confirming that the region supports the largest known population of the species, including 55 breeding pairs and 104 juveniles. The team also found that the species is thriving outside protected areas, often nesting in the cavities of trees along the border of forests and agricultural lands. Like the small, cavity-nesting owls HawkWatch International studies in our Following Forest Owls program, these owls depend on these natural cavities, meaning that protecting these trees is a top conservation priority.

Kaushal and his team also built strong relationships with the Gujarat Forest Department, local schools, and bird guides to foster community-led conservation. Events such as Forest Owlet Conservation Day and the Dangs Bird Festival brought hundreds of learners and researchers together to celebrate and learn about raptor ecology. Kaushal hopes to expand habitat monitoring, train local guides, and raise awareness about the importance of protecting the Forest Owlet and the forests in which they nest.

Kaushal and his team created a Forest Owlet poster, seen here translated into English

The Future of the Global Raptor Research & Conservation Grant

We are incredibly impressed by the knowledge gaps that the recipients of the Global Raptor Research & Conservation Grant have closed over the last 18 months, especially in light of all the adversity they have faced. While we are thrilled to have played a small role in these global raptor research and conservation efforts, we are concerned that many recipients have struggled to meet their objectives due to global instability.

Given this feedback, HawkWatch International has decided to award one fewer grant during the 2025-2026 grant cycle, but increase awards by $1,000, to a maximum award of $3,500. In doing so, we hope to provide more meaningful support to the researchers we partner with each year through the Global Raptor Research & Conservation Grant.

We recognize that this change will make the already competitive grant program even more competitive in the coming years. Each year, HawkWatch International receives far more proposals than we can currently afford to support. Since we provided our first grants in 2021, we have received over 120 qualified proposals from researchers around the world, and we truly wish we could support them all. If you are interested in learning more about how you can support global raptor research and conservation, please contact a member of HWI’s Administration and Development team to learn more by emailing hwi@hawkwatch.org. We look forward to working alongside you to build capacity for conservation around the world.

This blog was written by Kirsten Elliott, HWI’s Development & Communications Director, after synthesizing the reports provided by our grantees. You can learn more about our 2024 grantees here.