A “lifer” in the bird world is any bird that you’ve identified for the first time. Some people are listers, featured à la the recent documentary by Owen and Quentin Reiser, who collect new birds like Pokémon. Everyone has different criteria for what makes their list, such as only counting birds they’ve seen, while others include birds they’ve heard. Some feel that keeping lists takes you out of the moment and prevents genuine appreciation of the birds. Something we can all agree on, though, is that there is nothing quite like seeing a species you have never seen before. Regardless of your level of birding experience, you are always going to be adding new lifers to your list. However, what that looks like will change the deeper you get into the hobby.

Whether you’re a beginner looking for your first bright red Northern Cardinal, or a more seasoned birder looking for the fluffy, and disappearing, Spotted Owl, we’ve got some tips and tricks to help you on your way.

Don’t Skip the Training Arc

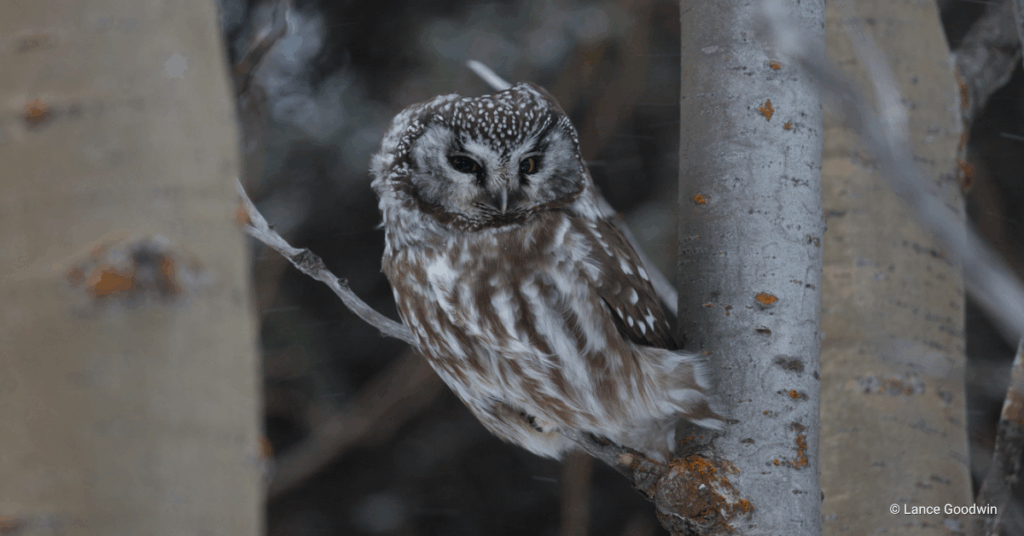

If you’re just getting started birding, you need to learn the basics. You wouldn’t try to make it to the NBA without knowing how to dribble a basketball, so don’t try to track down a Northern Saw-whet Owl when you can’t find or identify an American Goldfinch. What is exciting about being a beginner is that nearly every bird you see will be a lifer, giving you a ton of momentum at the start.

Start with the backyard birds, buy a pair of binoculars, grab a few ID guides (you can find our favorites for raptors on our store), learn the field marks, and download Merlin to familiarize yourself with bird calls. Most importantly, keep practicing. So much of bird identification isn’t something you can learn in a book or from an app. You might know hypothetically that a Sharp-shinned Hawk flies with “quick, snappy wing beats” compared to a Cooper’s Hawk that has more “stiff, powerful wing beats,” but what does that truly look like? The more chances you have to get eyes on the same species, the more you’ll start to recognize flight patterns, vocalizations, and field marks.

Another method some birders use is taking pictures of the birds they see and then identifying them at home. This can be especially helpful at the start when you aren’t as confident about your identification skills. However, you’ll want to set your expectations low on quality, as taking a picture of a tiny, fast-moving bird can be maddening.

Is Your Lifer a Local?

Once you’ve put in the labor to learn the basics and spent a fair amount of time birding in your own state, it is time to pick your dream species. After putting in the legwork, you’ll be better prepared to start traveling outside the state, country, or to seek out hard-to-find birds in your area.

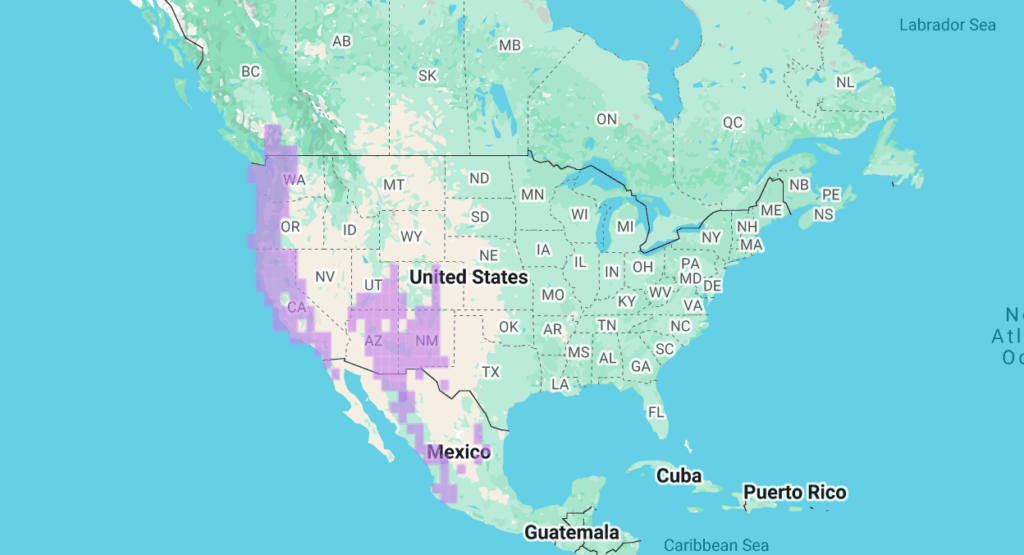

For rare birds in your area, like vagrants, join rare bird alert Facebook groups in your state, and turn on notifications for rare bird alerts in your county on eBird. The app will notify you if anything unique drops by. You can also use the eBird website to see where other birders have reported your desired species. Regions marked in a darker color indicate a high number of sightings, providing you with more specific locations to visit.

Lastly, birding is better together! Not only do you get the chance to socialize with fellow bird lovers, but you also get to learn from them. Your fellow bird club members have a wealth of knowledge of your local area and may be able to provide you with tips or potential locations to find your next local lifer. Plus, participating in birding clubs provides you with more eyes to spot birds you might have otherwise missed. To find a birding club near you, I recommend starting with your local Audubon chapter or searching for birding groups on Facebook. There are also national birding clubs, such as the Feminist Birding Club, which may have a chapter in your area. The American Bird Conservancy has a great resource listing birding clubs by state, which you can find here.

Traveling for Your Lifer

To find a lifter outside of your area, start with the range map. Ask yourself, do I need to cross state or country lines to see this bird? Is it the right time of year to see this bird? What about the right time of day? Going through this checklist will prevent you from traveling far and wide, only to realize that your potential lifer is a winter resident in the state you’re in, and you’re visiting in the summer.

One way that you can guarantee adding lifers to your list is by hiring a private guide or signing up for a group tour. Typically, your guide will ask about the species or types of birds you are interested in seeing and tailor your trip accordingly. This isn’t always the most affordable option, but having someone with local knowledge and a specialized career in identifying wildlife is undoubtedly a huge asset when trying to track down lifers.

You’re Here, Now What?

Unless you have the best of luck, just showing up at the location you’ve selected doesn’t mean you are going to magically stumble upon your lifer. Whether you’re traveling far away or visiting your local nature reserve, take a look at your field guides to learn about your bird’s behavior and preferences. Knowing the bird’s behavior and how ecosystems function will improve your chances and help you gain a better appreciation for all these birds contribute to our world, not just your life list.

If it is a warbler, you’re going to want to look high up into the tree tops, where you will discover the pain that is “warbler neck.” If it is an Elf Owl, keep an eye out for white wash, look for holes in trees or cacti, listen for their distinctively maniacal “laughing” call, and learn what defeat feels like. Just ask our Executive Director, Nikki Wayment, who has been skunked on eight trips to the Chiricahua Mountains—a great place to spot Elf Owls. You could say that Elf Owls have become her “nemesis bird,” a term of endearment birders use to describe birds they’ve gone looking for multiple times, and come back empty-handed.

Make Use of Migration

We may be a bit biased, but fall and spring migrations are among the best times of the year. Birds that you won’t typically see in your state or country fly through and provide a fleeting opportunity to see a high diversity of species at once. This is when you will see Snowy Owls cross into the lower 48, or when you can visit a hawkwatch site along a migration corridor to see hundreds, if not hundreds of thousands, of raptors migrate by. To find a count site near you, visit www.hawkcount.org, or to learn more about our sites, click here.

Bird Ethically

You will likely spend a considerable amount of time without seeing a single sign of your target species. That can be part of the fun, and what makes finding your bird so special, but it can also be wildly frustrating. This is when you may be tempted to use playback or “pishing”, where you play recordings or imitate bird calls in hopes that your goal species will reply or even draw birds towards you. These techniques, however, are controversial as they can cause stress to the birds by making them think there is a potential predator nearby, or by wasting energy to investigate your call. We recommend following the American Birding Association’s code of ethics, which advises using these tactics with caution and moderation.

Rare birds that are often considered desirable lifers are often species at risk. Species with low or declining populations, like the California Condor or the Whooping Crane, are particularly vulnerable to disturbances. As you should with all birds, but especially at-risk ones, keep a safe distance away, do not disturb them while they are nesting, and never bait them for your photo op. Please refrain from reporting the locations of threatened species to minimize potential disturbance by other birders. Owls are also common lifers due to their secretive and nocturnal nature, which makes them more challenging to find. Should you encounter one, please be wary of a camera flash’s impact on them. As bird enthusiasts, we should prioritize the preservation of a bird’s health and safety over simply checking them off our lists.

I hope that with the help of this guide, you’ll find your next lifer in no time! Best of luck and happy birdwatching. If you’d like to join us for a guided trip to a migration site or on a general birding tour, join our newsletter to stay in the know: https://hawkwatch.org/newsletter/

This blog was written by Sammy Riccio, HWI’s Communications Manager. You can learn more about Sammy here.