The Flores Hawk-eagle is ranked as the most understudied and threatened accipiter in the world (Buechley et al. 2021; RCPI 0.95). In an effort to learn more about this Critically Endangered species and enhance their conservation, we have partnered with Usep Suparman and his team at the Raptor Conservation Society in Indonesia, who have been working on the ground to locate nests and raise awareness of the species in the local communities.

It is estimated that only around 200 mature individuals, or 100 pairs remain. In thick forests, nests are not easy to find but over the past 10 years, Usep’s team has located 20 nests. They have also come face-to-face with threats to the species, which include extensive deforestation, illegal gold mining, and persecution. To inform conservation we really need to know more about this elusive bird. How large are home ranges? How does ranging behavior change between seasons? What are their habitat preferences? With this in mind we set out to initiate a GPS tracking project. For the past two years we have been supporting Usep’s team to find and monitor nests and we have been waiting for a suitable opportunity to deploy the first GPS tag.

Earlier this year, the local community at Kaowa on Sumbawa Island, West Nusa Tenggara, notified the team of a new nest, in a known territory that has been monitored since 2020. In this territory, the eagles have built a new nest in another tree every year and successfully reared a chick three times. Flores Hawk-eagles only lay one egg per breeding attempt. This year the nest was monitored by Afran and Abdul Azis from the Sindikat Fotografer Wildlife Bima – Dompu, and local conservation groups at Kaowa. Kaowa is nestled against the mountain and its inhabitants rely almost entirely on farming corn for their livelihoods. Unfortunately, this is driving deforestation. Even on the steepest mountain slopes, the forest is disappearing to make way for a monoculture of corn. This year the eagles’ nest was found on the edge of a small patch of forest, in a tree that was dangerously close to being cut down. The team negotiated with the community to save this tree but we don’t know how long that will last.

As the chick grew this year the monitoring team was sending me regular updates. It was a gamble to pack my bags and gear to head to Sumbawa, to hopefully GPS tag an eagle, but it was clear that we weren’t going to get a better opportunity than this.

Usep and I met in Bima, the largest city on Sumbawa. A hustle-bustle of a town, hot and humid, with the usual race of scooters and cars, it was my first taste of Indonesia. From there we gathered supplies, and headed up the winding mountain road to the village. We were welcomed to a wooden house on stilts, where the rest of the monitoring team were gathering. High level communication was tricky since we didn’t have a common language. But everyone was excited to break the ice by meeting my one-year-old daughter; “hello baby, what is your name” became a regular exchange.

After sharing a meal of rice, dried fish and boiled eggs, we packed our essential gear into backpacks and headed out to the forest, with an estimate of spending up to three days camping in order to catch an eagle, locally known in Bahasa as ‘Elang Flores.’ The walk from the forest to our camp took us along steep paths through the corn fields. We were heading into rural Indonesia, and I had no idea what to expect. We passed local families who were busy harvesting dried corn cobs, they had cheerful exchanges with our team and paid us surprisingly little attention otherwise. We set up our camp on the only relatively flat area of ground around. On either side of us, the forest had been replaced by corn fields, but we had the shade of some remaining tall trees. Below us was the patch of forest home to the eagles. By the time we arrived, the night closed in, and after another large portion of rice, we curled up in our tents, full of excitement for what tomorrow might bring.

Those first three days in the forest came and went. We put in trapping efforts, but we weren’t successful. I spent time watching the nest and got to observe the adult eagles bringing prey, mostly lizards, to the chick. It was an unbelievable experience. But it was tough, the forest is humid and full of biting ants and mosquitos. The only source of water was an hour’s scramble down a steep slope, which I never had time to do, so we were sweaty and dirty. The team carried water up for drinking, and kept us fed on rice and noodles. They took turns entertaining my daughter and proudly carried her around whenever she allowed. On the third morning, I skidded down a slope chasing monkeys away from the trap, and as I landed, scraping the skin off the palm of my hand, I started to wonder if we would ever catch the eagle…

By our fourth day, we were running out of supplies, and we were planning a re-supply mission back to the village. I got up early to set up the trap one more time and start the vigil. The monkeys hadn’t come by yet, and I wasn’t being eaten alive either. Just maybe there was a chance. I could barely believe it when the female eagle came by and complied with our plans. After carefully removing her from the trap, I carried her back to our camp, where we fitted her with a 30g GPS tag and took morphological measurements; some of the first for the species.

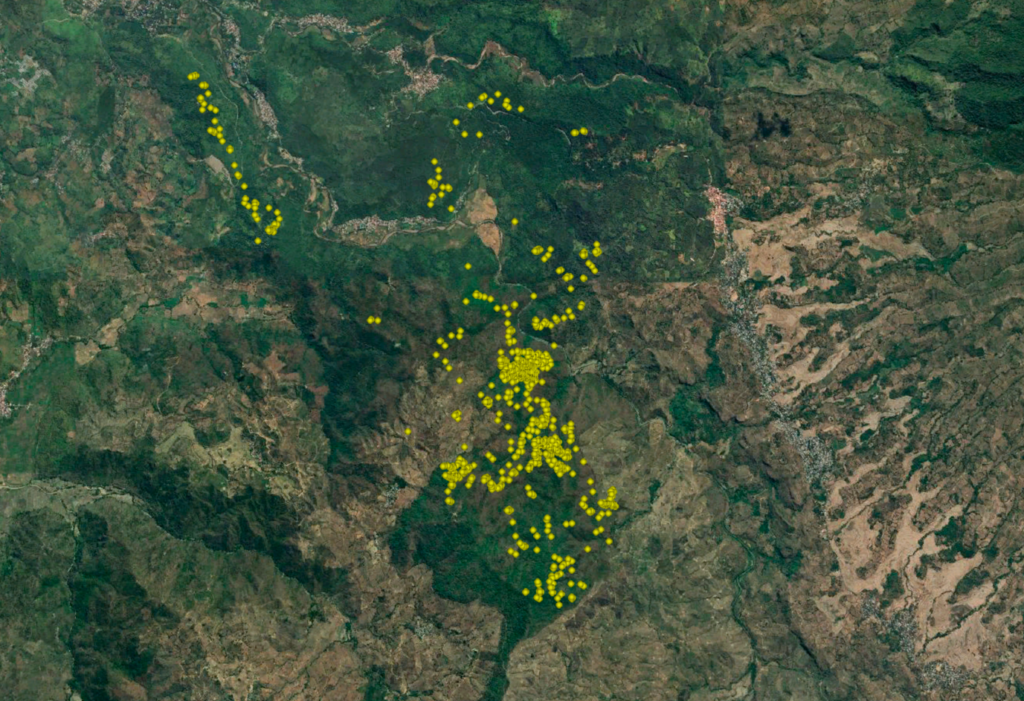

Even prior to tagging, the local team had named this eagle Paninta, meaning ‘Village Ruler’. Seeing her fly off, fitted with her tag, was a culmination of a lot of hard work, particularly by the local team. It was a really special moment and a privilege to work with such a rare species. Later that day, as we finished packing up our camp, we saw her with her mate soaring together over the forest, and although we waved her a goodbye of sorts, I have been checking on her every day since through her tracking data.

PC: Usep Suparman

PC: Stephen Wessels

We look forward to sharing more about our partner programs in the future! If you want to be the first to know, sign up for our newsletter here.

This blog was written by Dr. Megan Murgatroyd, HWI’s Associate Director of African and Asian Programs. You can learn more about Meg here.

Photo credit in order: Usep Suparman and Stephen Wessels.