Monitoring raptor populations is a long game. Here at HawkWatch International, we try not to put too much emphasis on what happens in any particular year, given the fluctuations that can happen due to a wide variety of conditions like drought, fire, prey populations, and more. That said, the past two years (2021-2022) stand out for the Golden Eagles nesting in Utah’s West Desert. And what we’ve documented is cause for concern.

Long-Term Monitoring Through the Years

To set the stage, consider that we have been intensively monitoring Golden Eagles in the West Desert in partnership with the U.S. Army’s Dugway Proving Ground and local eagle bander Kent Keller since 2013 (and Kent has been monitoring nests and banding eagles since the late 1970s). “Intensively” means not only watching hundreds of territories spread over many thousands of square miles (see how we monitor nests here), but also working with numerous partners to count jackrabbits, the Golden’s preferred prey, each spring. It includes hiking to the top of cliffs to rappel into nests to place satellite tracking devices on 97 nestlings, and “readable” color bands on 259 nestlings. More recently, it has involved taking blood and samples from 77 nestlings and placing cameras in nests as part of Dustin Maloney’s Ph.D. research to better understand nestling health and survivorship. Did I mention that we intensively monitor these eagles?

The Status of West Desert Eagles

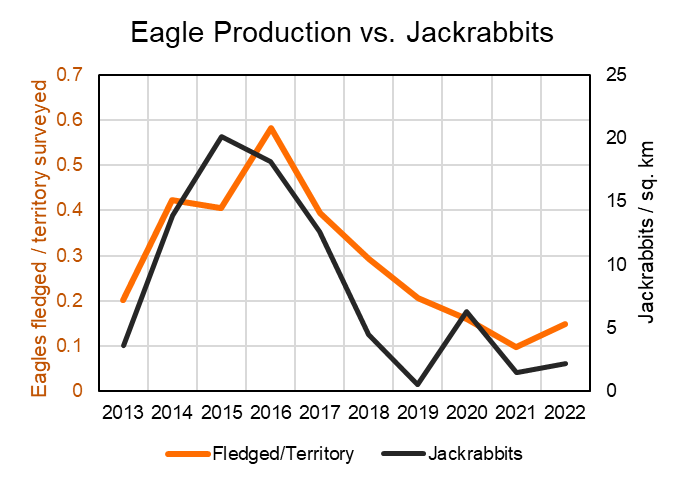

We now know that all of North America likely supports less than 60,000 Golden Eagles! That’s fewer eagles than fans at an average college football game! In 2015, the Golden Eagle was added to Utah’s “Species of Greatest Conservation Need” list, based on historic nesting data compiled by HawkWatch International that suggested eagle breeding activity declined in 2008 after widespread fires and shrub loss. More recently, a highly fatal rabbit hemorrhagic disease called RHDV2 was introduced into Utah toward the end of the 2020 nesting season. As you’ve likely heard, Utah is also in a drought. These things have all compounded, leading to two years in a row of very low Golden Eagle productivity (see figure).

What we saw in 2021, right after RHDV2 knocked the rabbit numbers back down, is that only 1 chick survived to the end of the nestling period (fledged) for every 10 territories surveyed! Eagles are long-lived birds and are used to weathering the ups and downs of prey and weather, with many birds choosing to forego nesting in “tough” years. Unfortunately, it seems like tough years are becoming more common in relation to human-causes, like introduced plants (cheatgrass), introduced diseases (RHDV2), and climate change. In addition, too many West Desert eagles that survive the nestling period are perishing due to vehicle strikes (9% of tracked-bird deaths) and other human-related causes. For example, in August of this year alone, 3 of our tracked eagles were struck by cars in Nevada and Wyoming.

What Can We Do?

By now you’ve likely heard the dire predictions for the Great Salt Lake and Lake Powell, that the fire season is longer and more intense, and other concerning trends like the one shared here about the Golden Eagles of the West Desert. There certainly are abundant reasons for concern, as we recently highlighted for eagles in this news article. But it isn’t all doom and gloom. There are things that we are doing and more that we can do with your help. First, HawkWatch International and partners are committed to continuing the vital monitoring of this species and their jackrabbit prey into the foreseeable future. Second, we are actively involved in the relocation of roadkill deer, an important food resource for eagles in winter when live prey is less available. We recently finished a 5-year study on how to make roadkill safe for scavenging eagles (e.g, see this publication) and are applying those findings in central Utah. We are also undertaking a new 4-year study to determine if adding roadkill deer to the remote West Desert can increase Golden Eagle winter fitness and reproductive potential (see photo below).

Third, HWI is working with partners to protect the most important intact eagle nesting areas, while also helping to guide restoration efforts that will plant 10s of thousands of shrubs in areas previously occupied by nesting eagles. This is also a long game, possibly taking 20-40 years to realize the shrub stature and cover necessary to support healthy prey populations and eagles. In the meantime, supplemental feeding might just be the key to sustaining eagles while we continue to keep close tabs on these magnificent birds. This is the hope that we ask you to consider supporting.

This blog was written by Dr. Steve Slater, HWI’s Conservation Science Director. You can learn more about Steve here.