Last year, we joined the Raptor Conservation Internship with HawkWatch International, which is an incredible opportunity for early career biologists. Not only did we get the opportunity to do hands-on fieldwork, but we also conducted our own research using a decade’s worth of data collected by the program. Each year since 2014, the CARES (Cavity Adopting Raptor Ecology Studies) program team, which includes HWI biologists and our amazing Community Scientist volunteers, regularly monitor over 500 nest boxes across the Salt Lake Valley to check the status of eggs and, subsequently, nestlings throughout the breeding season. The project spans habitats from urban parks to suburban backyards to cattle ranches and wildlife refuges. To track and identify kestrels individually, all kestrels from the nest boxes we monitor are given both numbered color bands (e.g. ‘Yellow ABW’) that can be read from a distance and metal USGS bands. When we do see kestrels out in the world, we are able to read their color band; we call that “resighting a banded kestrel.”

This is where our intern projects come into play. Jasmine was interested in nesting site fidelity, which is the tendency for individuals to return to the same nest locations each year, while Jess wanted to create a complete database of kestrel family lineages. Both projects meant organizing years of banding data and nesting history, which totaled 3,904 American Kestrels banded since the beginning of the CARES project in 2014. The more kestrel resights we were able to link together, the more excited we got about banding the nestlings and creating a family tree. This meant it was very important to identify if nesting parents were banded and, if so, who those parents were. This is where Jasmine began looking at site fidelity. At the end of each season, banded fledglings disperse to establish their own territories in subsequent seasons with their identification in tow. Many kestrels banded as nestlings will be seen nesting nearby the following year, but in our field season, we discovered an interesting exception.

After reading the color band of an adult female at one box, we discovered she hatched and was banded in that same box the previous year, which is a first in our study system. After spending another week trying to identify her mate, we finally spotted his color band and realized he ALSO was banded at that same box the year before. Not only was this the only example of kestrels not dispersing from their natal site that we found in the entire study, but it was also the first record of inbreeding for our program. By the end of the season, we ended up banding five healthy nestlings and hope to see them at their own nest boxes next season.

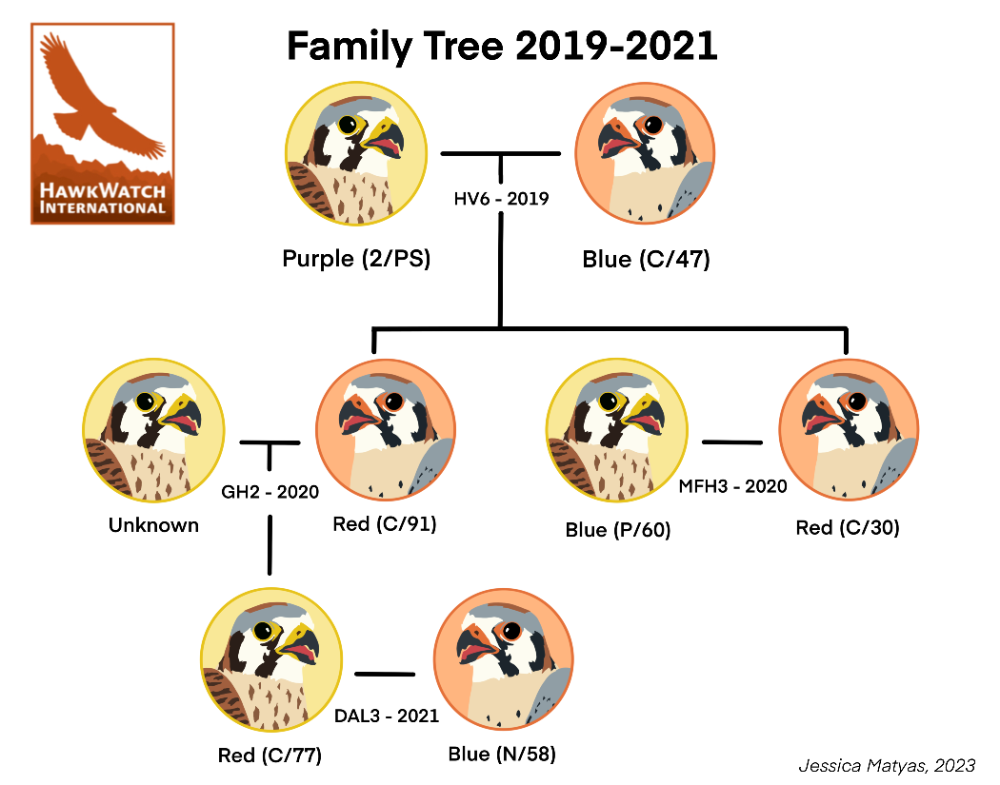

By the end of the 2023 season, we identified 57 previously banded birds and tracked their lineages and birthplaces across the duration of the long-term study. One of the more exciting life histories we uncovered was that of ‘Red (K/07)’, a female that had five nesting attempts after being banded as a nestling in 2015. She is the most prolific known breeder in the study system, with 16 recorded offspring! Our combined internship projects gave the project so much new information about kestrel lineage! Jess ended up finding the longest traceable kestrel lineage, with four generations spanning from 2019-2021. Jasmine’s project found that the original male of that lineage, ‘Blue (C/47)’, was found in subsequent years never nesting more than a mile from his first observed nesting site. Being able to build so many connections between kestrels banded throughout the years could only be done through the opportunities in a long-term monitoring project like this one.

Our season as interns with HWI’s CARES program was absolutely incredible. We learned so much and were so excited that our projects demonstrated the power of long-term monitoring programs. We hope that next season even more connections can be made and the kestrel family tree keeps growing.

This blog was written by former HWI Raptor Conservation Interns Jasmine Ruiz and Jess Matyas. You can learn more about them in this blog.